JavaScript Primitive and Non-Primitive Data Types Explained

A simple personal note about JavaScript data types, focusing on primitive and non-primitive values, memory behavior, and common pitfalls.

This article is written as my personal learning notes while deepening my JavaScript knowledge. Hopefully it can also be useful for anyone who reads it.

Understanding JavaScript Data Types

In JavaScript, every value has a type. At a high level, data types can be grouped into:

- Primitive

- Non-Primitive (Reference Types)

This difference affects:

- How data is stored in memory

- How values are copied

- How equality comparison works

Primitive Data Types and Immutability

A good way to understand primitive values is to think of them as photocopies. When you assign a primitive value, JavaScript copies the value, not the memory location. Primitive data types are immutable (cannot be changed directly).

Primitive types in JavaScript:

stringnumberbooleannullundefinedsymbolbigint

Analogy: Money and Photocopy

let uangAsli = 100000; // original money

let fotokopi = uangAsli; // copy of the value

fotokopi = 50000;

console.log(uangAsli); // 100000 (not affected)

console.log(fotokopi); // 50000Each variable has its own independent copy.

Primitive = Copy by Value

let x = 5;

let y = x; // y gets a COPY of 5

y = 10;

console.log(x); // 5

console.log(y); // 10Important points:

- Value is copied

- No shared memory

- No side effect

Non-Primitive Data Types and Mutability

Objects work very differently. Instead of copying the value, JavaScript copies the reference. Non-primitive types are mutable and stored as references.

Common non-primitive types:

objectarrayfunction

Analogy: Address, Not the House

When assigning an object:

- You copy the address

- Not the actual data

Object = Copy by Reference

let objA = { nilai: 5 };

let objB = objA; // objB gets the SAME reference

objB.nilai = 10;

console.log(objA.nilai); // 10

console.log(objB.nilai); // 10Both variables point to the same object in memory. This is why objects are:

- Mutable

- Easily shared

- Easy to accidentally break

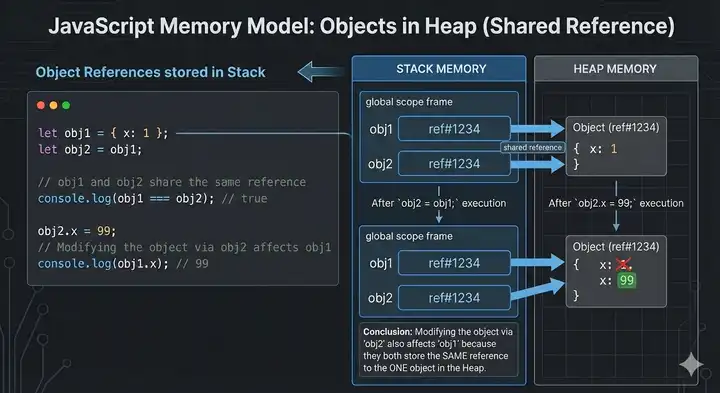

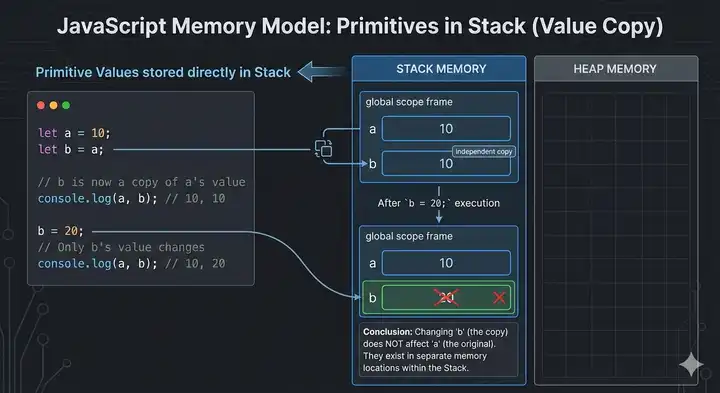

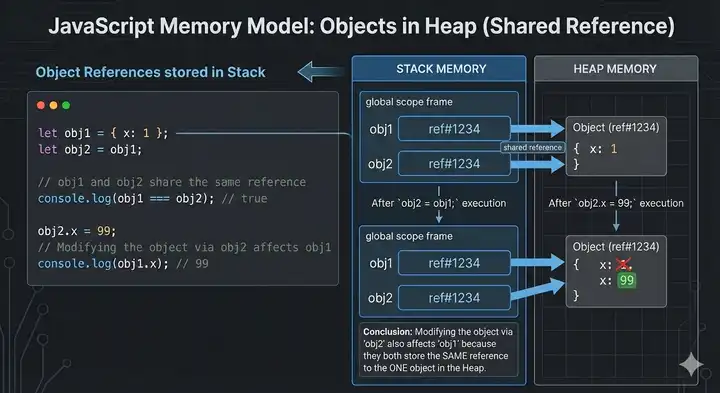

How JavaScript Stores Primitive vs Non-Primitive Values (Stack vs Heap)

Think in two layers:

Stack

- Stores primitive values directly

- Stores references for objects

- Fast and short-lived

Heap

- Stores actual object data

- Shared and long-lived

- Accessed via reference

Primitive in Stack (Value Copy)

let a = 10;

let b = a;

b = 20;Memory idea:

a→ 10b→ 10 (separate copy)

Changing one does not affect the other.

Object in Heap (Shared Reference)

let obj1 = { x: 1 };

let obj2 = obj1;Memory idea:

obj1→ reference →{ x: 1 }obj2→ same reference →{ x: 1 }

obj2.x = 99;

console.log(obj1.x); // 99const with Primitive vs Object (Common Confusion)

const means cannot reassign, not cannot mutate.

const + Primitive

const angka = 5;

angka = 10; // ERRORPrimitive value cannot be reassigned.

const + Object

const obj = { nilai: 5 };

obj.nilai = 10; // ALLOWED

obj = { lain: 1 }; // ERRORExplanation:

- Reference is constant

- Object content is mutable

Key Mental Rule (Very Important)

Primitive = copied value (safe, independent)

Object = shared reference (mutable, risky)

If you remember this rule, many JavaScript bugs suddenly make sense.

Equality Comparison (== vs ===) with Different Data Types

== (loose equality)

- Does type coercion

0 == "0"; // true

null == undefined; // true=== (strict equality)

- No type coercion

- Recommended

0 === "0"; // falseObject comparison

{} === {}; // falseBecause references are compared, not values.

Common Bugs & Solutions Related to Data Types

Below are common JavaScript bugs caused by misunderstanding primitive vs reference behavior, plus simple solutions.

Bug 1: Unexpected Mutation

Problem:

Array methods like push, pop, splice mutate the original array.

const arr = [1, 2];

const newArr = arr;

newArr.push(3);

console.log(arr); // [1, 2, 3] (unexpected)Why it happens?? Arrays are objects → shared reference.

Solution: Create a new array instead of mutating the original.

const arr = [1, 2];

const newArr = [...arr, 3];

console.log(arr); // [1, 2]

console.log(newArr); // [1, 2, 3]Bug 2: Object Comparison Always Returns False

Problem: Two objects with the same content are not equal.

{} === {}; // falseWhy it happens?? Object comparison checks reference, not structure.

Solution 1: Simple comparison (small objects)

JSON.stringify(a) === JSON.stringify(b);Order-sensitive, not for complex cases.

Solution 2: Deep comparison (recommended)

_.isEqual(objA, objB); // LodashBug 3: Accidental Shared Reference (Default Parameters)

Problem: Default objects are shared and can be mutated.

const defaultConfig = { darkMode: false };

function init(config = defaultConfig) {

config.darkMode = true;

}

init();

console.log(defaultConfig.darkMode); // true (unexpected)Why it happens??

config receives a reference to the same object.

Solution 1: Create default inside function

function init(config) {

const safeConfig = config ?? { darkMode: false };

safeConfig.darkMode = true;

}Solution 2: Freeze default object

const defaultConfig = Object.freeze({ darkMode: false });Mutation will now fail (or be ignored in non-strict mode).

Bug 4: Mutating Object Passed to Function

Problem:

function update(user) {

user.age = 30;

}

const person = { age: 20 };

update(person);

console.log(person.age); // 30Solution: Work with a copy.

function update(user) {

return { ...user, age: 30 };

}Tips for Working with Data Types in JavaScript

- Prefer

constto avoid accidental reassignment - Use

===instead of== - Be careful when passing objects to functions

- Clone objects/arrays when needed:

const copy = { ...original };

const arrCopy = [...arr];- Always remember: objects are references

Final Notes

Understanding primitive vs non-primitive types helps a lot when:

- Debugging weird bugs

- Working with state (React, Vue, etc.)

- Reasoning about performance and memory

This note is mainly for myself, but if it helps you too, that’s a bonus